The String

Oscar first introduced himself to me on a beautiful sunny day in the early and snowy winter.

I was struck by how close he came to me, and how he seemed small and conspicuously alone.

In retrospect, at the time, it felt a bit like looking in a mirror-perfect reflection of a calm lake.

A friend later told me that he likely had been abandoned by his flock, since Canadian Geese are usually social animals. I didn’t know if that was true, but the possibility wrenched my heart.

I felt captivated by him for a while. When geese have approached me in the past, usually they’ve been hissing at me to give them food or stay away from their families, but Oscar just seemed like he wanted to connect. If he did want food, he was being very polite about it.

I started seeing him in the same spot almost every day on my walking path. Each time, I felt a knot of concern in my chest. It just felt like something wasn’t right about him out there, on the ice, not flying, all alone.

I started feeding him a little. I had some healthy crackers, apple that I cut into pieces, and raisins, and was pleased to see that he liked all three, in that order of preference.

I was worried that he wasn’t getting enough to eat in the winter where he was. I didn’t see a whole lot of anything that looked like food. I could have been completely wrong about this… there might have been enough grass in the lake somewhere… but on some cold days, I saw him wandering around the ice chunks just pecking around, and it seemed odd to me.

I soon noticed that he had something hanging from his body. It looked to me like a fishing lure, but I wasn’t sure. I tried to reach for him, but he was quite quick and understandably didn’t trust me to touch him.

I managed to see, on a video I took of him, in a freeze-frame, his wing outstretched with a string clearly bound in it. And it was clear in slow motion video that he could extend one wing more than the other.

It then seemed pretty obvious to me that he couldn’t fly, and that’s why he was alone… because of this piece of string tangled in his wing. As soon as I saw that, my heart broke.

Seeing myself

At the time, my self-identification with this goose was largely subconscious. But in retrospect, I felt a deep kinship with him and his unfortunate circumstance.

Oscar came into my life at the right time, a couple of winters ago, after I had returned from a migration of my own. It had been about 16 months since I had left my long-term, familiar, full-time job as a college mental health counselor and moved to New Zealand, 6000 miles away, to try to make a long-distance relationship work.

It didn’t. And I had to return after a year.

It felt like a grand experiment that had failed, after I’d put a huge investment on the line.

I returned to my stomping grounds in the mountains and undertook a daily healing routine in nature. I ran, meditated, ate, slept, and occasionally made a new friend.

I don’t know how this string became tangled in his wing, but I was sure it was accidental. When he was swimming, paddling, diving for food, or whatever else he was doing on that unfortunate fateful day, he certainly didn’t plan to get hindered in a way that would threaten his quality of life, and perhaps his life itself. He was simply, I’m sure, trying to live, to take reasonable chances to grow… to be the best goose he could be.

That was my mindset when I’d left a familiar cocoon of security in which I’d felt largely stagnant for years. It took a long time vacillating between remaining there and taking a giant leap into the unknown, because the unknown was uncertain, with risks of great pain and sorrow that I couldn’t even really imagine at the time. At 39, I hadn’t taken a big leap like that in a long time. I had almost forgotten how. And I didn’t feel quite the same resilience, energy level, and seemingly limitless time for recovery that I felt in my 20s, when I had uprooted myself several times without much apprehension or hesitation.

It took meeting someone who lived in another country, and enduring a mostly long distance relationship for two years, with all the sadness and longing that that entailed, to get me to face my fear of leaving the stagnant cocoon and leaping into the unknown.

It was not, of course, with the idea of failing, but with hope that I was about to soar into a new and better life that would endure for decades and catapult me to new heights of happiness and self-actualization.

I did have quite a bit of apprehension at the time too. Maybe that was my deeper wisdom trying to tell me that my grand plan was not the way. Or maybe it was just typical self doubt and anxiety. Perhaps some of both. I didn’t know at the time. All I knew was that I could not stand at this crossroads for another year, working an old job that had lost it’s luster — and having a partner in New Zealand. Sometimes in life we have to choose, ready or not, and hope that the rewards will outweigh the costs of our big decisions.

Birds similarly migrate out of necessity and for opportunity. They can’t stay where they are in the winter because it’s too cold and there’s not enough food. And yet, the journey to fly for thousands of miles has risks. Migratory birds can die from exhaustion and starvation, get lost if stars aren’t visible to navigate by, collide with objects, and die in bad storms. Apparently getting a string trapped in one’s wing during a pit stop could be another danger on the list. So either way, there is a risk.

I wondered if this goose had headed South in early fall from Canada. Some neighbors would later tell me that they had seen him here for a few months. Did he get stuck here, midway to his final destination? Would he stay stuck instead of being able to return north to breed in the spring? How long could he just paddle around here by himself with no flock and no mate? What kind of a goose life was that?

I thought of my last few months in New Zealand before returning home. It wasn’t clear to me – then either – what the right course of action was. Transferring my career as a marriage and family therapist to New Zealand was proving to be far more difficult that I’d hoped, given that marriage and family therapy is not a recognized license there. I still had hope, and then the covid pandemic hit, and my attempts to get licensed as a psychologist there went from a crawl to a halt. Worldwide lockdowns and disease anxiety put critical pressure on millions of already strained relationships, including mine. I spent several months killing time, feeling rather stranded. I often coped by riding my mountain bike 13 kilometers each way in stormy weather to the beach and going on 10 kilometer barefoot runs, to return exhausted, and do it again the next day. I at least had nature, the pristine sea and crisp air, and the cold wind and rain on my face, to hold me in the eternal now.

There was a way back, but it was another one-way door. I’d have to get a one-way flight back to America, and start over, and I knew I didn’t have the will or the resources – inner or outer – to return to New Zealand again. It wasn’t a decision to take lightly. Several months later my partner and I had our final big talk and agreed that it wasn’t working between us, or for me, and that I needed to leave. It was very painful for us both, since we both always had the best of intentions, as we’d often remind each other. We parted on good terms and remain friends.

Traveling across the world during the pandemic because my new life didn’t pan out as expected was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.

The net

The name Oscar came from my neighbor who knew a farm goose named Oscar a long time ago when he was a kid. Over the next few weeks I would eventually see other neighbors who had noticed the goose and bequeathed it with different names. One was Bob. I forget the other. They were all male names. Was the goose a male? Who knew? Oscar could very easily have been a female, I still have no idea. Choosing “his” gender was a bit arbitrary. But I supposed it facilitated my projection of myself on to him, which was therapeutic to me at the time.

As soon as I saw the string tangled in his wing in the video, I was hit with a torrent of thoughts about catching him so that I could get the string off of him and restore his flight, and allow him to be a fully functioning goose again. Problem solving is one thing my mind does when I perceive suffering, my own or that of another.

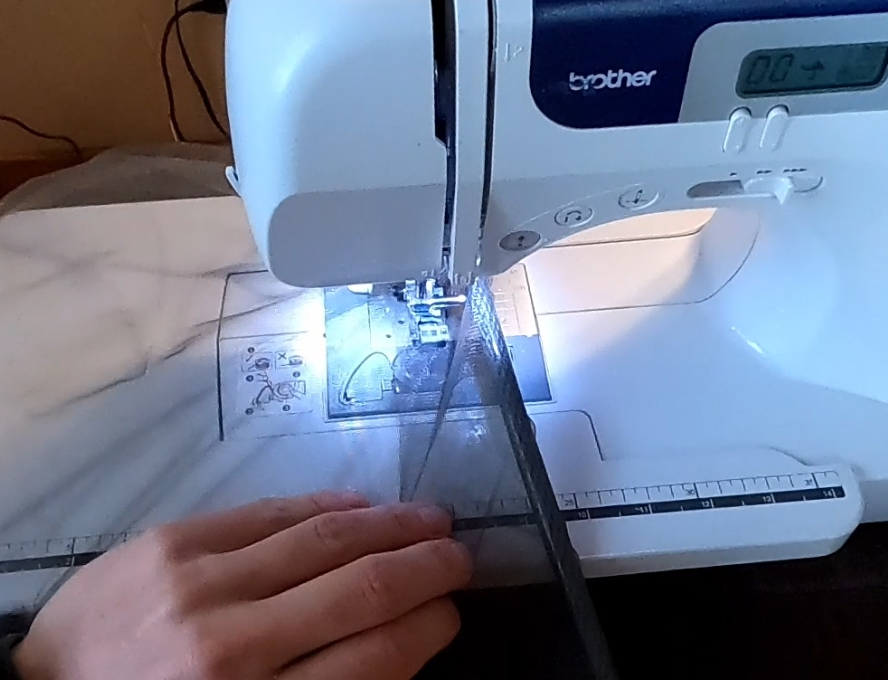

I had some mosquito netting and a sewing machine for making my own backpacking gear. My first attempt to help Oscar was sewing a net that was weighted at the opening by a circular cable so I could throw it over him.

It didn’t work. He was too fast, and there was too much air drag on the netting to throw over him, and I only managed a couple of attempts before he wised up to my agenda and started keeping a conservative distance from me. Of course he still stayed in the vicinity for crackers, which I’d been using as bait.

I tried again, probably the next day. I tripped and fell in the snow, which was too soft and deep for me to run downhill after him. Even with his hindered wing, he could glide across the ground a lot faster than I could move. I attempted a second throw, having to wait longer for him to approach as his desire for crackers slowly surpassed his suspicion of my intentions. I was even less close this time, and was starting to give up on the throw net idea.

The risk of accepting help

I reflected on how much easier this would be if I spoke goose, or if Oscar understood English and also believed in the sincerity of my desire to help.

From my point of view, I was offering life-saving help. From Oscar’s I was trying to harm him. How was he interpreting the crackers, I wondered? Did he think, sophisticatedly, that they were bait I was using so I could eat him? Or in his little bird mind was I intermittently switching back and forth from benevolent bestower of crackers to dangerous goose predator every few minutes? What kind of relationship was developing here?

How many times do we reject help because we perceive it as a threat? Why is accepting help so hard?

One reason is that help often comes with strings attached (pun intended). We’ve all been on the bad side of a transaction before. We’ve all felt that we took the chance to be helped and, in the long run, were worse off for one reason or another.

To the extent that we’ve been offered help with an unfair and surprise bill to pay later, we tend to be suspicious. And when this happened repeatedly to us in childhood, at our most vulnerable, it can have long lasting effects on trust.

Oscar’s fear was biological and innate, fearing instinctively that he’d have to pay with his little goose life for anything I could offer.

As humans, our barriers to accepting help tend to be psychological.

It’s often hard to accept help because we fear becoming reliant on another person. We have to admit that we can’t do something ourselves, and that can bring our existential dependence on others to the forefront of our consciousness. Dependence puts our survival in the hands of others – hands that are outside of our control. It implies that those who hold our need fulfillment in their hands could withdraw support at any time, abandoning us in a time of need.

Many of us fear that asking for help, or receiving too much help, can result in the other person feeling burdened, resenting us and withdrawing. And that could leave us vulnerable at a time that we were coming to rely on support instead of enduring perpetual self-reliance and self-protection, which modern culture tends to encourage.

Trust is the felt sense that we can exchange support with someone in a mutually beneficial way. Trust is delicate, and needs to be earned, because there also exists the reality of exploitative, predatory, and parasitic relationships in which one being benefits at the expense of another.

We intuitively know that if we accept help from another person, there is both opportunity to establish a symbiotic relationship, and danger of being exploited. We’re naturally more aversive to loss than we are drawn to gain, so we often focus on avoiding the danger more than seizing the opportunity.

Brainstorming

Having taken it upon myself to keep Oscar healthy while I allowed my subconscious mind to plot his emancipation, I did some Internet searching on what geese like to eat.

Oscar’s preferences had little correlation with the recommendations I saw online. I read that geese like spinach, cabbage and carrots, for example, but he was having none of those. Maybe they were for a different goose species. I continued to feed him corn kernels and sliced apples and then follow those with some whole-grain crackers, which he clearly loved. I read that it’s not great to feed geese a lot of bread products for the same reason that processed foods aren’t great for humans. But they made good bait, and I figured he could use some comfort food for a while given his situation.

I told some people about Oscar, and picked their brains for ideas for his rescue. Someone recommended I contact the local wildlife rescue center, which I did, and they said they could help an injured animal that I brought in, but that they didn’t have the resources to send people out to catch a hard-to-catch goose. I tried the rescue center in the nearest big city, and got the same recommendation. The person I spoke to was very sympathetic but basically told me it was up to me to catch the goose and bring it in.

The stick and box

The next idea that occurred to me to try was the classic box-propped-up-by-a-stick trap. Like perhaps the one you’d see in an old Bugs Bunny or Roadrunner cartoon.

I spent some time crafting a box of sorts out of a large baseball batting net propped up by a ski pole. The net box, which needed some enhancements to eliminate open sides and corners, was lent to me by my neighbor (the one who named Oscar) who also became interested in freeing Oscar, and sometimes helped me in my goose catching attempts.

The idea was that Oscar would get underneath it to retrieve some crackers, and I could pull a string attached to the ski pole and let the net fall over him.

This didn’t work either. He would not get close enough to the center of it. I was impressed and surprised at his apparent spacial awareness; he seemed to have a pretty good sense of how close he could get without getting trapped underneath it if it happened to tip over. I again found myself wondering about the extent and nature of his intelligence.

He did, however, get full of crackers, and the bait became less interesting to him, so the attempt ended.

Sometimes after my plans would be foiled, I’d feel frustrated and inwardly debate giving up, thinking, “I don’t have time for wild goose chases! It’s a bird. I eat birds all the time. Why does this one matter?”

But almost every day when I went out on walks or runs, I’d keep seeing him out there …not flying… walking around on ice… alone… and my empathy and determination to free his wing would kick back in.

On days when I didn’t have the time or creativity for another possible solution, I’d visit him for a meal and a nonverbal conversation. His presence was comforting to me. I wondered if mine was for him too (when I wasn’t trying to catch him)… or if his approaching me from hundreds of feet away was purely out of my salience as a source of calories. At least on my end, I was feeling a relationship of sorts start to form. He was becoming important to me, and that gave my life some extra meaning at a time when I frankly needed more of that.

I started getting into the habit of swimming in the cold water around this time, and I wondered if that helped him trust me more, perhaps seeing me as a fellow winter water foul.

The lasso

In the end, sometimes the best solutions are the simplest. My father actually suggested using a lasso to snare his foot. This seemed unrealistic to me at first. But after the last net trap failed, I got on Google on a whim, and in three minutes learned how to tie a lasso with the cord I already had out, and set a wide circle in the snow with some crackers in the middle.

To my amazement, it worked like a charm on the 1st try. His large foot sank down a bit in the snow while the string stayed on the surface, so that upon lifting his leg, his webbed toes caught underneath the string, cinching it closed around his narrow ankle, and he was snared.

My neighbor and I had been trying to catch him together this particular day, and we went through the process of removing the string from him. It needed to be cut in a few different places, and it was clear while thoroughly inspecting Oscar’s wing that it had damaged some of his feathers.

Oscar was pretty alarmed and stressed out during the process. I imagined him thinking, “What a day! What did I do in my past life? First this confounded string and now these humans are going to eat me for dinner!”

We tried to be soft spoken and comforting, and I’d like to believe that calmed him down.

Hurt vs harm

Oscar, of course, didn’t know that we intended to help him and that it might hurt a little bit, or make him afraid. He assumed, being a goose, that we intended harm.

What exactly IS the difference between hurt and harm?

I’m not sure it’s always obvious in a given intervention what the outcome will be.

One of the hard things about asking for help is not so much the fear of the help hurting but the fear of the help causing harm, leaving us worse off, even when the helper has good intentions.

And even when the helper is us helping ourselves.

We tend to help ourselves right away in the painless ways.

But the more pain it takes to make a change, the more likely we are to push it off until later.

Sometimes the way out of a problem is so painful that it doesn’t appear on the radar of our consciousness.

That’s often the moment that people have their first therapy appointment. They know there’s a problem, but they don’t see a viable solution. If they did, they’d have implemented it already.

These kinds of crossroads involve facing some of our deepest fears and venturing into the unknown, often impelled out of desperation and crisis.

They are the kinds of crossroads that a bird faces when it begins a risky migration, or when it encounters danger or injury on the way.

They are the kinds of crossroads that I faced when I decided to move to New Zealand, and the kind that faced when I had to return and start over.

They involve pain either way, whether we respond to the call to action and go through the risky ordeal of transformation, or we decide to remain in the painful status quo.

To modify the well known Anais Nin quote,

“And the time came when the pain of being tangled up in a string for months at a cold lake outweighed the pain of having two humans with extra time on their hands lasso your goose foot and hold you for an uncomfortably long time while they searched through your feathers to cut the string off.”

We took our time to make sure we got all the string pieces out, surmising that we might not have another chance if we missed any of it. I had no idea if Oscar would ever trust me again to get close enough.

After a thorough check, we cut off the lasso from his leg and let him go. The difference was immediate and uplifting in more ways than one. He was able to take off and glide for a couple hundred feet right away, before he quickly settled back down on the water.

It was an exhilarating moment for all of us, I’m sure. I felt real joy in my now lighter heart, seeing such a tangible benefit and feeling such a strong conviction that this was going to change the life and experience for this little avian being.

Cutting the strings that bind us

I was a little worried that Oscar wouldn’t understand what we had done and would just think that we were messing with him, but less than an hour later he came back and walked up to me. Did he know? Or did he just want more food?

He followed me along the shore of the lake for a while and swam back and forth in front of me while I sat there on the beach.

I don’t know if he knew. But at least we were still friends.

I had been actually pretty stressed about this goose, which seemed silly at times, considering I’m not even a vegetarian and eat chicken weekly. This was one bird among billions. But there was something about seeing this animal every day on my walk, all alone, just struggling to survive… or at least that was the story in my head. I don’t know how much he was really struggling. But clearly he wasn’t thriving.

But after we got the string off him, I stopped worrying right away, and noticed that the stress simply let go on it’s own like a tangled string that has been cut off, because I knew I had done what I could for him, and the rest was up to him and nature.

I reflected on how sometimes outside help from others can remove a hindrance that we can’t remove ourselves.

I thought of a chapter from Irvin Yalom’s book, The Gift of Therapy, in which he talks about the “inbuilt propensity toward self-realization” that is active and working as long as obstacles to our growth are removed. Here’s a quote from this section:

“If obstacles are removed, the individual will develop into a mature, fully realized adult, just as an acorn will develop into an oak tree… what a wonderful, liberating, and clarifying image. It forever changed my approach to psychotherapy by offering a new vision of my work. My task was to remove obstacles blocking my patient’s path. I did not have to do the entire job. I did not have to inspirit the patient with a desire to grow, with curiosity, will, zest for life, caring, loyalty, or any of the myriad of the characteristics that make us fully human. No, what I had to do was identify and remove obstacles. The rest would follow automatically, fueled by the self actualizing forces within the patient.”

This is the truth that I felt every time I saw Oscar. Here was this perfectly made being that had an obstacle that was conspicuously blocking his path. How can a juvenile goose (Oscar was small) become a fully fledged and thriving adult goose if he cannot fly?

While not all geese migrate, many do, and those who don’t surely need the ability to quickly take off to escape predators or get to new and varied food sources, or simply to properly exercise their bodies the way they were designed to for optimal health.

Canadian geese are pair-bonding birds that choose a mate for life, so both females and males presumably put some care and discernment into who they choose for a mate. How could Oscar (whether Oscar was a he or a she) be chosen for a mate without the fundamental ability to fly?

Flying, migrating, fleeing danger, finding food, breeding, and simply experiencing the joy of healthy goose living were all inbuilt in Oscar, as the potentiality for an oak tree is inbuilt in an acorn. But the string – this simple, thin, deceptively pernicious string in his wing – was preventing all of that.

Psychological strings

It begs the question how much human (and other animal) potential is thwarted by such hindrances. In my mind, Oscar’s string became a metaphor for the psychological wounds and defenses that prevent us from being at our healthiest and most vibrant. They are the psychological knots and tangles that constrict our hearts, torment our minds, and disrupt our harmony with the world.

An injury or wound is something that happens to us, whereas a defense is a response to prevent further injury later. For example, being exploited as a child is a wound, which could result in various defenses including a tendency to isolate, dominate, or placate, depending on the nuances and particularities of the individual’s environment and temperament. Defenses always serve some purpose of protection, but also almost invariably become hindrances. The defense of placating others, for example, may be a necessary survival strategy for a time in the life of a child, but later causes problems as the people pleasing becomes overgeneralized and applied to situations that might actually require assertiveness or self-reliance.

It is interesting to consider whether or not the building of defenses is something we do to ourselves or something that is done to us. The trauma that the defenses stem from was done to us, and the defenses seem to self-assemble from nowhere, especially when we’re children (which is when defense foundations are typically laid down). Was Oscar’s string that was stuck in his wing for months something that was thrust upon him by fate, or something that he waddled into himself?

As we discover our collection of subconscious, life-hindering defenses, perhaps during our first foray into therapy as adults, are we to conclude that we are their creators — that we walked into them as Oscar ostensibly walked into that confounded string, or that they were thrust upon us by others who, intentionally or accidentally injured us?

Perhaps one’s answer depends on the extent to which one believes that we have free will, and how much free will we have at each stage of life. I tend to think that we have less free will as young children, since so much of our experience is subconscious in youth. However, I’m not sure the answer matters that much to me, because however I look at it, the way forward is the same. We must do what we can for ourselves, and sometimes for others if we are able, to get these life-suffocating strings off of us.

On a personal and intuitive level, I had been seeing the string around Oscar’s wing as a metaphor for what I had gone through recently, and for what I think what everyone goes through at some point, probably at multiple points in our lives.

There were times when I saw him and would start to cry, identifying with what I imagined him to be going through: the sorrow of the loss of what could have been, if not for an injury. I was feeling the recognition of universal and timeless vulnerability of all animals… the danger of being blindsided by misfortune without the needed strength or external help to recover… and what that has been like for every sentient being that has ever existed in the universe… for every being that was ever wounded without a known route to healing… for every being that was hindered without a clear hope for freedom.

It was a perfect combination of feeling my own and Oscar’s combined suffering, for instilling in me a deeper, experiential understanding of universal pain and compassion.

After my goal of immigrating to New Zealand and living “happily ever after” didn’t work out, it was like a string had tangled itself in my wing for a while. There were a lot of tough narratives going around in my head. I had never really failed that spectacularly before in my life, and it was very humbling. I had left a stable job with substantial status, told my coworkers and friends that I was moving across the world indefinitely, sold my car, and spent significant time, money, and energy on a great migration. I didn’t get grounded and stranded on the way due to a string, but it felt that I wasn’t strong enough to endure the unexpected weather I encountered, and was forced to turn back — tired, bruised, and worn out, with what felt at the time like nothing to show for it.

The “string” in my case was a narrative of shame and failure for daring to try to fly by taking such a big and sudden leap at middle age. For taking a big gamble and losing. For not being stronger, more resilient, more tenacious, or… something that my inner critic was telling me that I “should” have been.

Our strings can go by many labels: self-doubt, insecurity, inadequacy, fear, anxiety, inhibition, distrust, envy, and myriad others, depending on the interplay between each person’s own trauma history and their natural essence.

Now I am grateful that I have a lot to show for my experience, and that it was a necessary and important journey for prying me out of my smaller and cozy prior life situation, and for teaching me about opportunity, risk, struggle, defeat, grace, asking for help, healing, and metamorphosis.

It took a lot of my own work, and help from others, to cut off the metaphorical strings from myself.

To be more accurate, the string didn’t all come from recent events. The psychological strings of shame and unworthiness really begin early in life, and it’s easy to forget about them when we are doing well measured according to society’s external criteria. As long as we have enough external successes and sufficient approval from others as compensatory distractions, we don’t have to notice the inner hindrances that keep us tied down emotionally and spiritually.

It’s when we don’t live up to the expectations of our family, our society, or ourselves, that we feel the strings acutely, as we stand there alone and exposed, aware of what has always been there and that we managed to forget, day after day.

Oscar was probably not aware of his string every minute of the day, but it was there, nonetheless, holding him back. So it is with the psychological traumas and baggage that we carry around with us — outside of our awareness — until we try to fly in a new way.

I’m not 100% string free and I doubt that anyone is. But I do believe that I have a few less strings tangling me up as a result of trying to fly in a big way and faltering, which forced me to see for the first time some strings that I didn’t know were there, giving me the choice to work on severing them, often with the assistance of others.

And one important piece of my own string disentanglement was cutting off Oscar’s string. More accurately, it was the entire process of meeting him, comprehending his predicament, feeling compassion, caring about his future as I saw him each day on my walk, making plans and implementing efforts to help him, persevering, and eventually succeeding.

Sometimes it’s easier to care for someone or something else more than it is to care for ourselves. Parents know this, as they find themselves making surprisingly heroic efforts to give their children the nurturance they need to thrive. Pet owners often know this when they become more sad at their dog’s or cat’s illness or injury than they are at their own. And I may have found myself putting more effort into project goose freedom for a few weeks than I was into my own unbinding. Maybe sometimes pain is more obvious when we’re viewing it from the outside than when we’re experiencing it from the inside.

But a magical and wonderful phenomenon is that it matters less than one would think whether we hone our compassion and caring skills on ourselves or on another suffering being.

I was helped by Oscar as much as he was helped by me, because he motivated me to practice compassionate caring and action in a way that I wasn’t particularly motivated to practice on myself at the time. But compassion is compassion, and compassion practice is transferable from others to oneself.

This is something I’ve learned during my time as a therapist and coach as well. When I show up for clients and I’m present, it helps me practice showing up and being present for myself. When I pay close attention to another human being’s experience with empathy and curiosity, it helps me become a more skillful observer of human experience, including my own. When a client and I focus on their anxiety or depression and discover some of the causes and potential solutions, I come to understand the times that I fall toward fear and shutdown, and what to do about them.

Helping Oscar was an experiential reminder to myself that I am able to facilitate flourishing and be a force for good… whether it was for Oscar or for myself.

Most change requires effort. If feeling better were that easy, no one would ever feel bad. If kicking bad habits and forming good ones were easy, there’d be no bad habits left. It takes flexing of the willpower muscles and activating of our discipline circuits to pull ourselves up, or to pull another up. We have to muster the courage to look at often overwhelming problems and goals long enough to break them down into smaller, less overwhelming, achievable steps, and tackle them one at a time.

“I need to free Oscar… maybe a net… okay I can find that netting.”

Any time we persevere toward a goal, whether it’s an inner goal like thinking positive thoughts or an outer goal like a business project or creative pursuit, we are an acorn slowly growing into the oak tree. We are a goose stretching its wings to try to break a string that is hindering us, or to fly for the first time after having the string cut off of us by a caring benefactor.

And, it’s reasonable and good to ask for help when we need it. If the other person chooses to give the help from a generous and compassionate heart, they will be helping themselves in doing so.

Epilogue

I saw Oscar from time to time after his unbinding, with less and less frequency.

As winter turned to spring, I was happy to see him with a couple of other, bigger geese. I knew it was him because he was smaller and he parted from the trio and made a bee line straight for me for food.

I didn’t like that the two bigger geese would push him out of the way to get the food I tossed for him, but I was happy that he at least seemed to have started integrating into a community.

Eventually I stopped seeing him around, or at least he stopped swimming up to me. I was a little sad but mostly happy. I figured that he found other geese to hang out with, and perhaps was venturing to new territory. As the months passed, I would see groups of them around and I couldn’t distinguish him from the others, if he was there.

Sometimes I would see a pair or a flock flying high overhead and wondered if he had recovered enough to do that — if one of them was him.

One day in the summer, I saw a goose who swam back and forth in front of me, and I wondered if it was him.

The next winter, the temperature and seasonal changes got me thinking of him again due to associations with the cold water, snow, and ice. I wondered if I would see him in the winter for some reason, such as a migratory pattern or stop. I didn’t see any geese alone that winter, and I’m glad because it probably means he was with other geese somewhere, perhaps in a warmer place.

I did see one or two pairs of geese during the following winter, on many occasions. I wondered if any of them were Oscar with a mate. Without the string and his behavior of swimming toward me, I wouldn’t have been able to distinguish him. Nevertheless, I liked the thought that he’d been able to find a mate after regaining his birth right of flight.

On a walk one cold winter day, I saw a huge flock of geese circle above the lake a couple of times, honking prolifically, as if a big group decision was being made. Then they flew off. I wondered if he was there among them. I hoped that, if so, he was happy, connected, and welcome in his community.

I told an uncle of mine about the goose, and he was moved by the story and the video of the string being cut off. He sent me a beautiful wooden carving of a Canadian goose that I now keep in plain sight, next to part of the actual string that bound Oscar for several wintery months. The carving and string is a reminder to me that we can become unhindered, sometimes with a bit of help from another, and sometimes by helping another.

Thank you for reading.

I wish you a life free from hindrances, and the help that you need along the way.